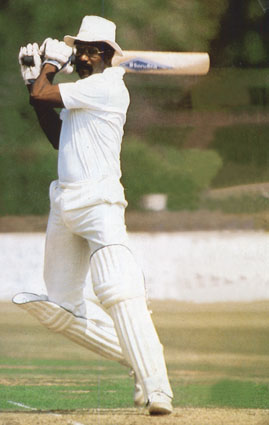

Lloyd: the cricketer

HE would amble to the wicket, often looking bemused as those eyes peered out through the spectacles which he wore all his playing life except for a short period when he experimented with contact lenses. He looked an amiable figure as he walked to the crease, apparently deep in thought. And then the fun would begin. He could hit the ball harder than most and carried a bat which was heavier than what most batsmen wielded. There were two or three rubbers grips round the handle which made it difficult for a great many players to even get their hands around it. His huge hands held the bat with no great difficulty.

Lloyd was a batsman who could destroy an attack; the difference between him and Richards was that he seemed to be almost apologetic for every stroke he made. Richards made no secret of his contempt for any form of bowling but Lloyd seemed a relatively humble figure as he waited for the bowler to arrive. Once the ball reached him, it was a different story; it would be screaming along the ground or hit hard and high, or met with a perfect forward defensive stroke. There was so much power in his hands that that forward prod sometimes went to the fence. He could hook with great power and he did not fear the bouncer.

Lloyd's height gave him tremendous reach and this was an advantage when it came to playing spin. He could meet the ball a long way down the track and smother the spin. But he was not averse to using his feet either and in his very first Test as captain gave Prasanna, Bedi and Chandrasekhar a taste of what he could do by smashing them all over the place while scoring 163 in the second innings at Bangalore. He did not hesitate to go down the track nor did he ever think twice about punishing the bowler from his crease.

At the start of his career, Lloyd was a pretty useful bowler and a cover fielder who was terrifyingly quick, good enough to be compared with Colin Bland and Paul Sheahan. But injury forced him to shift to the slips where he spent a great deal pouching difficult chances and easy ones too in those huge hands. There was a great deal of determination in him, a fire which burned, and made him want to push himself and his team to new heights. He fought back after sustaining a spinal injury in Australia in 1971, an injury which kept him in hospital for a month.

Many players have found the added burden of captaincy inhibiting their batting. Ian Botham is a case in point. Lloyd was as different as could be. He positively revelled in his batting and, in fact, has a higher average for the period when he was skipper than before that. He was never overawed by the situation and, though often finding himself with only tailenders for partners, ended up with three-figure scores quite often. His batting was destructive too and this helped the tailender who was partnering him to capitalise and record a good score as well.

Richards would often order his partner to stay there and not get out. Sobers would try to help his partner by using subtle gestures. The difference with Lloyd would be that he would counsel the man at the other end. Staying there while the captain made the runs then became an act of friendship and this was a totally different equation. He could ask this of his partner because he had demonstrated time and again that he would speak up when the interests of his team were harmed. There was no question of parochialism; if anybody had a problem it was more because of that individual's hang-ups than anything else.

In the main, Lloyd succeeded because he often made the runs which his teammates had failed to make. He led from the front and if he failed, then he did not gripe about others doing likewise. If he succeeded, he did not point to his success to porve that others were not doing their bit. To him, the argument ran thus -- the captain has to carry more weight than the others, else he would not be the leader. Simple and professional.

The late Michael Manley was one who understood West Indies cricket as few have. He was moved to write this dedication at the beginning of his seminal work A history of West Indies cricket:

To Learie Constantine who opened the door of

international cricket;

To George Headley who entered the building with such style;

To Frank Worrell who showed it could be occupied with distinction;

To Clive Lloyd who very nearly took permanent possession;

And, of course, to Garfield Sobers who dazzled all those who dwelt

therein with the range of his talents.

There is no better nor more eloquent tribute to Lloyd.