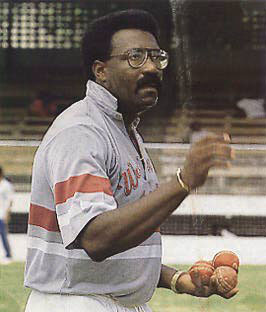

Lloyd: the leader

He has to be about half a dozen men, all rolled into one. He must have the nerve of a gambler, the poise of a financier, the human understanding of a psychologist, ten years more cricket knowledge than he can ever possess and the patience of a saint.- Gary Sobers in his book Advance about the qualities a West Indies captain needs to survive.

FROM a shy, gawky,

bespectacled youngster who could not hold his place in the team, Clive

Hubert Lloyd grew to become a captain who was looked up to by his

players. He was responsible for the longest run of success which any

team has known in international cricket. And he began working with a

team which had been soundly thrashed, a team which had a great deal of

self-doubt. From these beginnings, he forged a unit which was

unbeatable in conditions both at home and away, no matter the

opposition. He learnt from his mistakes and never repeated them. He

knew that playing attractive cricket and not winning meant being taken

lightly; he knew the West Indies had a reputation for this and was

determined that they would play their usual game and also take home the

spoils.

FROM a shy, gawky,

bespectacled youngster who could not hold his place in the team, Clive

Hubert Lloyd grew to become a captain who was looked up to by his

players. He was responsible for the longest run of success which any

team has known in international cricket. And he began working with a

team which had been soundly thrashed, a team which had a great deal of

self-doubt. From these beginnings, he forged a unit which was

unbeatable in conditions both at home and away, no matter the

opposition. He learnt from his mistakes and never repeated them. He

knew that playing attractive cricket and not winning meant being taken

lightly; he knew the West Indies had a reputation for this and was

determined that they would play their usual game and also take home the

spoils.

Lloyd's first Test provided him a memorable lesson about captaincy. The West Indies needed 192 to win in their second innings and four wickets went down before the team reached 100; Sobers and Lloyd came together and after the skipper had given the debutant his instructions, he added that they could get the runs quickly so that he could listen to the races on the radio as he had been given a hot tip! In his first Test, it appeared to him that his captain was more interested in winning at the races than the Test.

That tour proved successful for the West Indies who won two out of the three Tests. But there were things which the young Lloyd observed, things which were to stand him in good stead when he finally came to captain the team himself in 1974-75. The team won in 1966-67 because they were a better combination than India but there was little consultation about coping with the opposition, bad public relations, little application and professionalism and no team spirit. They were a disparate bunch of talented individuals and were led by a man who was head and shoulders above them.

These lessons were driven home when Lloyd played against England at home in 1967-68 and against Australia in 1968-69. He was surprised by Sobers's declaration in the fourth Test but to him the only point to be digested was that it was made without consulting any of the other members of the team. The batsmen had not been told about it, else the pair who had started that day at six for no loss would surely have scored faster; in two hours upto lunch the score had moved to 72 for one. This lack of communication bothered Lloyd and he noted it down for future reference. It was to prove useful. In Australia, the team which had a large number of aging stars, buckled under after winning the first Test; they only showed some resoluteness in the fourth Test but in all the others did not show the willingness to apply themselves and play. A large number got out to what could only be called outrageous strokes and they dropped over 30 catches in that series. More lessons for Lloyd.

When he was finally given the job of captain for the tour of India in 1974-75, he had a number of first-timers in his team, among them Vivian Richards. That tour was a success, with Lloyd toting up his first series win at 3-2. The World Cup which followed saw more success and then came the trough, one of those tours which shape a man's thinking for life, Australia in 1975-76. The West Indies came up against Lillee, Thomson and Gilmour. Pace and swing in abundance and a team which played real hard. They crumbled like ninepins and lost five Tests while winning one; this was the series after which some of the younger players needed help from a psychologist to boost their confidence. Lloyd realised that such an attack could well be the answer he was looking for.

The other deciding moment in Lloyd's career as skipper came in 1976 when he set India over 400 to win in the last innings on what was considered a spinner's wicket in Trinidad. He had three spinners in the side. They failed to even run India close with the visitors running out comfortable winners by six wickets. That, as far as Lloyd was concerned, was the end of an attack built around spin. He had seen Andy Roberts develop into a good pace bowler and had Michael Holding to partner him. The idea slowly crystallised -- a four-man pace attack that would give the batsmen on the opposing team no let-up. He did not mean to play foul but to play tough. The image of the West Indies as a team which played attractive cricket but went home losers was about to change once and for all.

From that point on, the four-pace attack was born. Lloyd was blessed with an abundance of superb pace bowlers who seemed to come off on some kind of never-ending assembly line -- and with glorious variety too. Roberts, Holding, Garner, Croft, Clarke, Marshall, Daniel, Baptiste, Davis, Walsh -- some were executioners, others part time players, some stayed for years, others not very long, but they all played their role in one way or the other. In England, they nicknamed Holding "whispering death", so quiet was his approach to the wicket; Marshall, after he developed into the fastest of them all , was simply nicknamed "death". Garner used his height to advantage, Croft bowled an awkward line, Marshall simply beat them all with speed and swing. Lloyd had his warheads and he used them as he saw fit.

Lloyd also had some of the best batsmen of the era in his team. Greenidge and Haynes were an opening partnership sans comparison. Richards could reduce any attack to a shambles. The steady Gomes and Logie both complemented the skipper's batting and he was one who performed exceedingly well with the bat during the years he was captain. He had excellent keepers in Murray and Dujon and the occasional spinner in Harper. Towards the end of his reign, younger players like Richardson also contributed their mite with the bat.

What then of his leadership? If he had all these bowlers and batsmen at his command, did one really need to be a leader of any calibre? Greenidge has carped about this, saying there were times when a pensioner could have captained the team, so good were they; Greenidge also points to the time in Australia in 1975-76 when he says Lloyd could do nothing to motivate the team. (Greenidge's views may be in part due to the fact that he knew he would never get a chance at the captaincy himself as he had been brought up in England). It is true that there were low points and Lloyd is quick to admit his failures; there were numerous reasons for the Australian embarrassment -- the superiority of the Australian attack, bad umpiring, bad starts, and the overuse of the hook shot when they were bounced.

But one cannot overlook the fact that Lloyd managed to weld the West Indies into a united team. He commanded respect from his players because he was willing to go out on a limb for them, fight for better pay and conditions and even quit the captaincy when he felt that players had not been picked for reasons other than their ability. He welcomed the Packer episode because he realised that the West Indies cricketers, arguably the most exciting bunch of players, were finally being paid what they were worth. More than that, they were being made aware that they were worth that much. Lloyd's strong point in this, as in everything, was that he was willing to take a stand and encourage his mates to follow him. A good number of them did.

Lloyd's tactic of unrelenting use of pace has also had its critics, with Gavaskar once accusing the West Indies captain of "barbarism." But to that, it must be said that any captain who had such bowlers at his command would use them; they did get carried away on occasion but Lloyd justified the use of the short-pitched delivery by pointing to the fact that there were laws against intimidation and the umpires were there to lay down the law. In short, if one does not want to feel the heat one should get out of the kitchen; cricket, at the highest level, is a tough game and those who cannot take the pace should not attempt to play. Lloyd was not prepared to be Mr Nice Guy and go home the loser; by his logic if one sent in a bowler at number three then that player should also be prepared to face bowling of the sort which a number three usually did.

The bunch of islanders who were known for their attractive cricket were slowly moulded into a team which began to be known as one which would push hard for victory, one which would not crumble under pressure, one which was devoted to the idea that winning was the sole thing in the game. There was hard-core professionalism and to achieve this Lloyd insisted on discipline, fitness and application. Sometimes, they fell apart but that was no disaster; they regrouped quickly and came back firing. There were times, as in England in 1976, when a careless remark was all the spark they needed. There were others when they needed no motivation other the fact that they were what they were -- a champion bunch who had a reputation to keep intact. Lloyd gave them pride in being a team, not a bunch of brilliant individuals; he gave them better pay and better conditions; he gave them something to play for more than the thrill of smashing the ball to the fence and being out next ball. He taught them that hard work was needed and sometimes hard work could triumph over talent which was not carefully used.

To the West Indies, cricket is more than a sport; it is the expression of a number of things which run deep, and hark back to the days when they were ruled by white men. There is a great deal about cricket which makes it a natural sport for the West Indians. But they never jelled together until Worrell came along; Lloyd was merely an extension of this philosophy and what he gave to West Indies cricket continues to shape the thinking behind the team to this day. In that lies his legacy.

This tribute to Lloyd would never have been possible without the help of Linus Fernandes