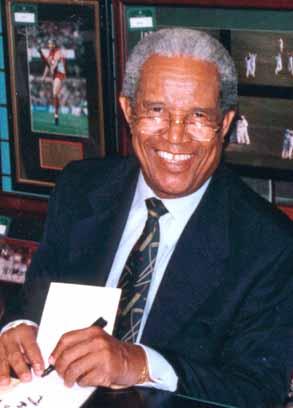

Sobers - the cricketer

HE WAS born with an

extra finger on each hand, as though the good Lord had already decided

that he would excel in a sport where the hands played a major role. The

presence of extra digits is also supposed to be a sign of luck.

HE WAS born with an

extra finger on each hand, as though the good Lord had already decided

that he would excel in a sport where the hands played a major role. The

presence of extra digits is also supposed to be a sign of luck.

But luck alone would never have taken him to the heights he scaled. Sir Garfield St Aubrun Sobers was that rare cricketer who turns up once in a generation, one who can excel in every way and still make it look simple. A man who could come in when the chips were down, hold his side together with a hundred or more, open the bowling, come on as second change as well and finally turn up out of nowhere to grab the slightest of chances and turn the match decisively his way. The word genius, a much misused one these days, is the only one which fits.

His appearance from the pavilion was enough to set bowlers on the opposite side a-thinking. The familiar toothless grin, two or three buttons undone, his sleeves rolled up, Sobers would stroll in, leaning over to the left ever so slightly as though the good Lord had gone on pouring the goodies down that side. Once at the crease, guard taken, he would proceed to disconcert the fastest of men by standing a good six inches in front of the crease. The ball came to him earlier, yet he was never at a loss to judge it; be it on the front foot or rocking back, he would give it the full treatment.

To

him a good cricketer was

one who could bat according to the

needs of the team and the situation in which it found itself. He

believed in playing an attacking game, entertaining people and never

thinking of avoiding defeat first. His watchword was to attack and win.

Yet, when the situation demanded, Sobers could be the most obdurate of

customers, playing carefully and using all his considerable skills to

occupy the crease as long as he could. Despite this, he was never

unattractive to watch, never a boring batsman, never a defensive

bowler.

To

him a good cricketer was

one who could bat according to the

needs of the team and the situation in which it found itself. He

believed in playing an attacking game, entertaining people and never

thinking of avoiding defeat first. His watchword was to attack and win.

Yet, when the situation demanded, Sobers could be the most obdurate of

customers, playing carefully and using all his considerable skills to

occupy the crease as long as he could. Despite this, he was never

unattractive to watch, never a boring batsman, never a defensive

bowler.

Which other captain, coming to the crease with his team at 102 for five and chasing 735 for a win, would put paid to the attacking field placed for him by dispatching the first five balls he faced to the fence? It required tremendous ability to do that, but it came naturally to Sobers. He could hit the ball with tremendous power, but he could also use his wrists so beautifully that the most indiscernible of flicks would see the ball speeding to the fence, a category of strokes that people took to calling not-a-man-move-shots. They simply raced away so fast, timed to perfection, that they were hitting the pickets before a man had moved.

Sobers was built like a perfect athlete, tall and lithe, and he had perfect technique. Rarely did he hit across the line. He played with a straight bat and his range of strokes was amazing; a bowler would often bowl the same ball to him six times in a day and find him playing a different stroke each time. There lay the touch of genius. He took three years after his Test debut before he made his first Test hundred but that knock will be remembered by everyone who has anything to do with the game; the record he set stood for 37 years.

Figures alone do not tell the whole story. It was not just the runs he made, it was the way he made them. Had he been conscious of records, mindful of keeping his own average higher or thinking of himself, his tally would have been much higher. To him, such considerations were anathema. The ball was there to be hit. He respected good bowlers but always let them know who was the master out in the centre. He enjoyed the mental tussle in the middle and if he came out second best was the first person to congratulate the man who had got his wicket.

Sobers was one of those rare cricketers who never waited for an umpire's finger to go up. If he had touched the ball and been caught, he would walk. There was one occasion in a Test against Australia when he walked even before Wally Grout had appealed. To him it was pointless walking only in cases where one had scored a century. There was no point in cheating and winning. If he had caught the ball cleanly, he let the batsman know it and if he had grassed it, then he was equally open about it. He was a sporting person to the core.

His method of captaincy is open to debate. His critics feel that he depended too much on having others follow his example; given his abilities, his act was extremely difficult to emulate. He captained teams which had some of the most talented cricketers of all time, yet he ended up losing a good many series. He took chances often to make the game interesting and try and prevent a stalemate; the one for which he is known best is the fourth Test of the 1968 series against England when he called his side in after they had reached 92 for two in the second innings; the West Indies had a first innings lead of 122. England had a sporting target and they reached it. Sobers was hanged in effigy and had he not been the player he was, he would have lost the captaincy. He tried his level best to redeem things by scoring 152 and 95 not out in the next Test, the last of the series, and taking three wickets in each innings, but England hung on for a draw.

Sobers played 86 Tests on the trot from 1954 onwards and would probably have continued playing without interruption but for being left out of the team in 1973 due to the whims of selectors who felt he had to prove his fitness. Arguably, he should have been willing to listen, but this was being said to a man who had time and again played for his country despite his body desperately crying out for rest. That series was against Australia and Ian Chappell, the Australian captain, was moved to comment that a series win against a West Indies team which did not include Sobers could not really be counted as a victory.

Sobers played his last Test the next year, leaving the arena at a time when he was still scoring runs. From 1966 onwards, a damaged shoulder had ensured that he would have to give up his chinaman and googly. Yet he was no mean bowler even at this stage; his Test best of six for 73 came in 1968-69 at Brisbane after 15 years of top-level cricket. That series, his last in Australia, was played against a team which was captained by one of the meanest captains of all time, Bill Lawry. The West Indies often had the upper hand in the five-match series but ended up losing 3-1 having dropped as many as 34 catches.

Sobers succeeded Worrell as captain and managed to hold the team together to some extent. The West Indies played attractive cricket under him but ended up losing quite often. Sobers was skipper for 39 Tests and he won nine of those and lost 10. Kanhai, who took over from him, did not stay long and the most famous of the West Indies skippers after Worrell, Clive Lloyd, took over in 1974 for the tour of India. Sobers played the last few Tests of his career under Kanhai.

It is 38 years since he retired from the game, yet few who saw him in action will forget the genius of the man who has been by far the best all-rounder which the game has produced. There was motion, grace and fluidity in his approach to the wicket, the reflexes of a panther, and a range of shots which few have displayed. He was the cricketer's cricketer. There will be no other like him.